Conor Murgatroyd

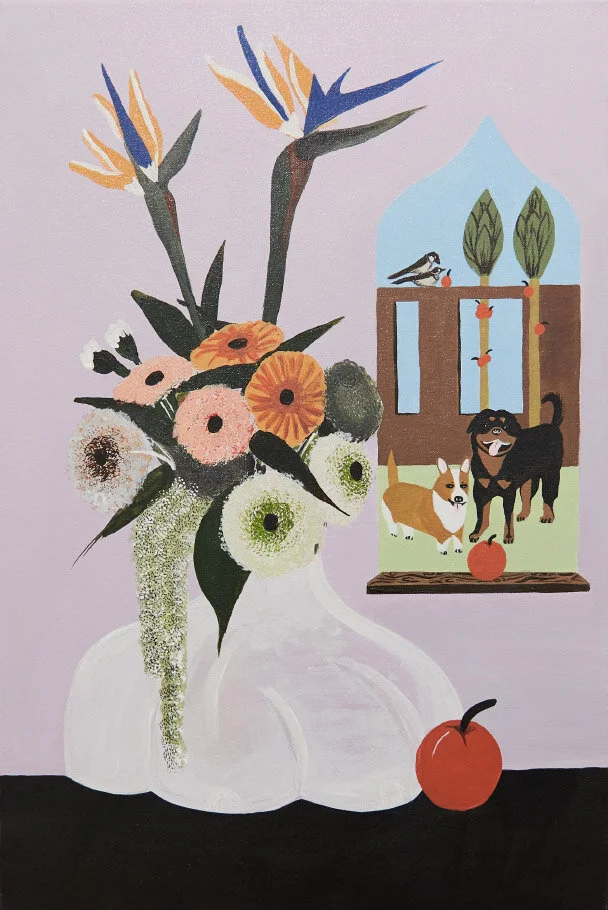

The weight of Conor Murgatroyd’s work might be missed at first glance; the non-threatening nature of his commonly used motifs such as flowers or family photographs, along with his frequent recourse to traditional” still lifes or like compositions, lends his work a visual levity.

Yet, under scrutiny, a far greater depth is revealed: his penchant for self-depricating double-entendre and irony, shared as if with a cheeky wink, as well as a deep and coloured understanding of history and context.

But to speak broadly of Conor’s work is to neglect the nuance that can be accessed through a close reading of his paintings; their power lies in small, thoughtful detail. In this vein, this can be demonstrated by focusing on two paintings in particular, both currently hung as a pair at Conor’s recent exhibition History’s Shadow Marks the Beginning with Battersea-based gallery Grove Collective: Listening to Sade (2021) and Self-Portrait with Tracksuit (2021).

Compositionally, the two make a natural couple, balanced equally by similarity and contrast. They are similar in size, and although both figures are seated at a desk, framed by an embedded image in the background, the sitter of Listening faces the viewer, while the sitter of Self-Portrait (ostensibly Murgatroyd himself) faces away. However, composition merely provides an entry point to a much larger dialogue between the two; it provides the scaffolding on which much deeper connections can be built. Take, for example, the Sade record placed on the right side of the mantle piece in Listening to Sade, along with the book marked SADE on the table in Self-Portrait.

The former, it would seem, is a rather straightforward reference to the British singer Sade, but then what is the book on the table? While there have been several books published on Sade the singer (all of which appear to be out of print), the more logical connection is of course the more literary of the Sades: the Marquis de Sade, the infamous French erotic writer for whom the term “sadist” was coined. Therein lies the kernel of Murgatroyd’s brilliance: his ability to lure the viewer into thinking they have his work understood, or worse yet, pinned down, only to exploit a simple heteronym to so quickly and effortlessly turn the tables. As soon as you think you’ve seen everything, Murgatroyd is quick to remind you that he is one step ahead.

Still, there is more. Among the books on the table in Self-Portrait are Scaffolding A-Z (a book which does not seem to have ever been published), along with books on Manet and flower arranging. Notably for an image in which the sitter faces away from the viewer, these titles reveal more of Murgatroyd’s past than any frontal image of him could – the former suggests his past as a builder, having worked construction before pursuing art full time, while the latter reflect a personal love of Manet, modernism, and art history writ large, along with his own motif of flower vases. Having ostensibly denied the viewer his own image in his self-portrait, Murgatroyd has left clues for the viewer to find themselves; clues, yes, about his history, but also about his future. Again, Murgatroyd proves his thinking to be well beyond only initial perception. Instead, he invites the viewer to simply keep up with his use of references, creating a remarkable – and enthralling – depth. For anyone who has ever called still lifes or portraiture “boring,” Conor Murgatroyd is here to tell you you’re not looking close enough. In an art world that has become all too dependent on the spectacle, there is finally an artist to encourage slow, thoughtful looking – who has the talent to create images that will only give us more with time.

words JACOB BARNES

What to read next