John Greenwood

Out of sight, out of mind; the subconscious accounts for 90% of the brain’s function, still its intricacies have not yet been fully discovered. Due to its complex nature, in combination with the growing effect of technology on human life, reexamining the repressed psyche has become increasingly engrossing, piquing the interest of nonspecialists and pundits alike.

In this spirit of inquiry and speculative research, English painter John Greenwood explores related matters across his monographic ‘I’ve got a massive subconscious’, at Richard Heller Gallery, Santa Monica. Throughout his decade-long career span, beginning with his participation in the inaugural Young British Artists exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, London in 1992, the artist has been fusing probes into uncharted territories of the mind with autobiographical examinations. Merging personal turmoil with his innermost thoughts, and drawing inspiration from biology, Dutch paintings, jewellery, flora and fauna, Greenwood exposes the microcosmic and macrocosmic, his practice a vehicle for studying worldly contradictions.

For his first monographic exhibition on American soil, Greenwood combines his curiosity in neuroscience and psychoanalysis with art history. On display are paintings he created during lockdown, a period of enforced seclusion, during which fears of contagion ran wild, parallel to his imagination. Outrage and disbelief with the troublesome state of affairs seeps into his canvases, where he digs deep in an effort to convey universal sentiments of fear, humor and struggle in the face of the absurd.

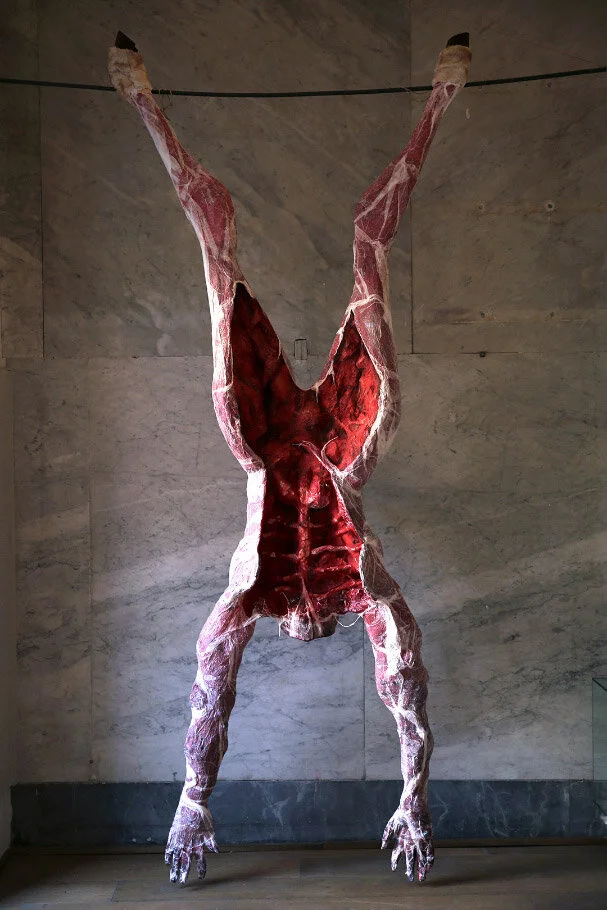

Greenwood’s paintings are intentionally hard to pin down, incessantly shifting between isolated portraiture, still life and crowded compositions. They are the consequence of a distillation process which begins with drawing, the most crucial step. His preliminary sketches are informed by artistic heritage, from Hieronymus Bosch’s surreal-scapes to Nychos the Weird’s graffiti. Mixing unorthodox references that feel both fabricated and natural at once, his resulting canvases are imbued with Old Masters’ dark tones, mischievous inventiveness, natural proportions and coat overlays. Greenwood portrays playful nightmares whilst teasing the viewer with an overwhelming confusion, a flurry of fear and a healthy dose of thrill. After four to five layers of oil, the outcome could pass for an e-reproduction, yet no digital tools were involved in its hand-painting. He further implements the construction of engine-like-entities to provoke fear of the unknown, the technological other, the monstrous machine.

The artist liberates himself from chromatic constraints and engages in an intuitive method of colour application, with balancing cool and warm tones as his only rule: bold syntheses of emeralds, magentas and navys heighten their intensity. Greenwood does not want to assign specific meaning to any shade, a freedom he bestows upon the audience, stressing that he is not a symbolist painter. An impeccable rendering of texture makes the objects jump out of the canvas, as if they were part of a tangible universe. By means of meticulous placement of light and shadow, Greenwood produces both cartoonish, two-dimensional paintings and realistic, three-dimensional ones. The white tiles in the background of his lifelike works help incorporate them into the viewer’s space, ready for hoarders to reach out and grab them.

The painter’s most defining accomplishments are likely his still lifes, which are anything but still. Inspired by Spanish bodegón depictions of food arrangements verging on the religiously symbolic, his lively interpretations of the inanimate appear as real, but aren’t. He describes these works as “a believable illusion of something that never existed”. The amalgams uncover the trappings of lust and luxury, outstretching themselves in areas too small to hold them. Things that, if one tries to touch, they’ll touch back; a feast for the eyes, as he calls it.

Greenwood insists that he does not seek to impose a narrative on his works. Fittingly, the titles do not serve an explanatory purpose. Poetic choices like ‘Always on My Mind’, ‘An Immaculate Misconception’ and ‘The Holy Hand Grenade’, are a reaction to some of the surprising realizations he has while listening to music when working. This way, he leaves the narrative open to interpretation, though the metamorphosis that takes place within them is more about disintegration than it is about growth, he claims. An unconventional pessimist, the artist faces his desperation head on with a sardonic grin.

With a taste for shapes that dance, Greenwood draws creative power from circuses, fairgrounds and other folk artefacts that mimic bodily activity - his figures are in perpetual flux. Their auras are anthropomorphic but not quite human, with a few isolated faces effortlessly catching the viewer’s eye. None of the works in the show are self-portraits, though the distorted visages do reflect his concerns and observations. By representing frowns next to smiles and furrowed brows near beaming eyes, the artist empowers the viewer to “choose their own adventure”, exposing both inner world and external appearance simultaneously; it is up to the observers to decide which possibilities they prefer. However, this isn’t an attempt to reveal a deeper reality about the human condition.

The artist is fascinated with pareidolia, the brain’s tendency to detect patterns that resemble the human face in the natural world. Making use of this stimulus, he assembles elaborate designs that approximate a mask from afar, but up close it becomes clear that it consists of simulated, non-human parts. By building a face from disparate articles, Greenwood conveys what he views as the essential instability at the core of our existence. In this way, he poses questions about personal identity and the fundamental illusion of human behaviour: the pretense of being categorizable whilst materialising out of a series of abstract processes that pretend to be definitive.

The artist’s relationship to space is a complicated one, changing from painting to painting; via the use of limited angle and painstaking technique, he ensnares his hybrid creatures in claustrophobic confines, while maintaining depth and scale ambiguous, baptizing his approach as “an implied disjuncture of scale to the cosmic”. Greenwood’s non-minimalist temperament peeks through the few cracks of the canvases, whose subjects are on the verge of spilling out. His still lifes illustrate creatures that should be inanimate - and therefore still - but are instead bobbling, dripping and oozing, ready to expand at any moment.

There are two discernible spatial routes; sterilized boxes and chaotic multiverses. For the former, he employs an enface, one-point perspective, utilizing a white-tiled grid for the background. The implication is that whatever is displayed on the canvas is, in a sense, a figment of the onlooker’s imagination. This is precisely articulated in ‘The Museum of Now’, where Greenwood compactly displays Frankensteinian artefacts located within the maniacally disinfected walls of what seems as a scientific laboratory. These frames, open only to the viewer’s side, are reminiscent of a prison cell or an asylum room, a slated locus from which there is no escape for its contents. For the latter, he wants the viewpoint to shift so rapidly that it’s destabilizing; an example of this inclination is ‘Ghost Machine’, a mayhem of color contrasts, distorted facial expressions and twisted veins. The manner in which the elements intertwine like tree branches, along with a warped perspective, produces a dizzying movement. Preoccupied with motion, the artist instills a flickering from one mood to another. Thus, he captures the permanence of impermanent entities, inquiring on transmutation, decay and death, while the physical objects on display remain perpetually unaltered.

John Greenwood’s paintings traverse fantasy and jest, using familiar art historical tropes from a range of both highbrow and lowbrow sources, including still life, moving image and street art. Hence, he has gone on to forge a contemporary painting practice grounded in Northern European tradition but operating within a context provided by polar opposites - beauty and vileness, comedy and tragedy, fecundity and futility. His humanoid portraits exist amid the real and imagined, his suffocating treatment of space demonstrates the eternal battle between microcosm and macrocosm. The constant in his canvases is the inclusion of the unidentifiable. Considered “unapologetically postmodern”, viewing Greenwood’s works is akin to having night terrors - except we are awake.

John Greenwood’s ‘I've Got a Massive Subconscious’ at Richard Heller Gallery, Santa Monica runs until 31st July.

What to read next