Ben Ditto

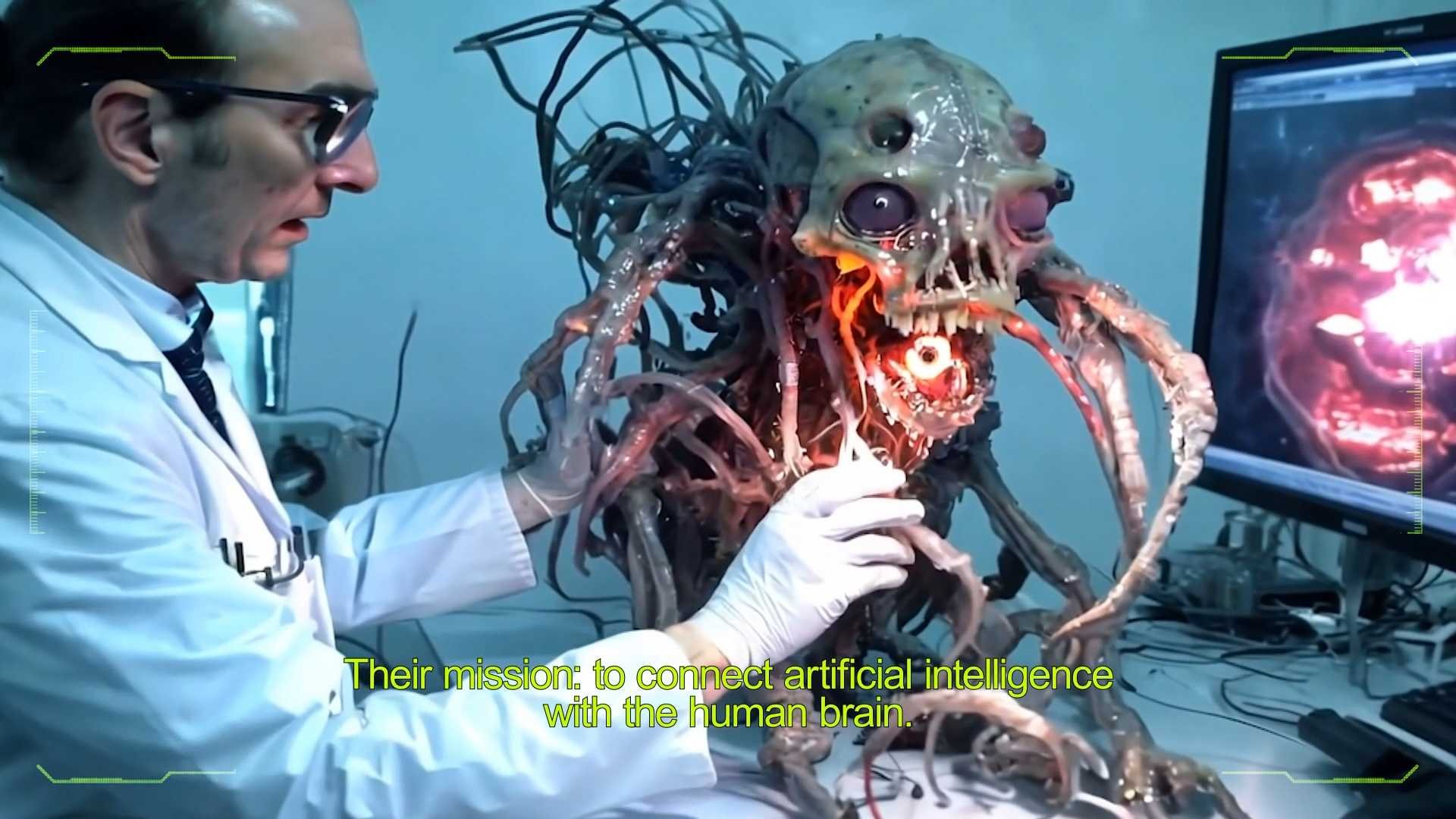

“Infesta” for Yaya Labs Hackathon with Umanesimo Artificiale by Cristina Dezi, Simone Restifo Pilato, Maximilian Prag and Gioele Villani

Ben Ditto, creative force behind Yaya Labs, offers a refreshingly candid take on technology’s evolution, grounded in both humor and insight. Sharing his past experiences in Milan—where a serious accident once colored his view of the city—Ditto opens with a mix of levity and sincerity. Shifting to AI, Ditto reflects on its current role in society, noting that while many predictions are panic-driven, real change will unfold in less sensational ways. At Yaya Labs, he uses speculative fiction as a framework to develop AI and robotics projects, including Desdemona, an AI-driven personality designed to engage both emotionally and culturally. Ditto’s Wetware Club builds on this idea by positioning artists’ unique creative processes as integral to future AI outputs, ensuring that human creativity remains central.

“Wetware Interface” by Connor Clarke for Yaya Labs

“Wetware Interface” by Connor Clarke for Yaya Labs

“Wetware Interface” by Connor Clarke for Yaya Labs

First, I want to ask you, how was your day? How did you find Milan upon your arrival, and how is everything going?

Thank you very much for meeting me; it's nice to see you. Milan is interesting.

I used to hate Milan because the first time I came here, I was in a bad traffic accident and ended up in the hospital for two weeks, having my leg reconstructed. Every time I've returned to Milan, I've tried to find something to like about it, and this time I managed.

I like it today. But someone almost hit me with a car yesterday. My colleague and I were crossing the road when someone came around the corner and accelerated towards us. So I nearly had my second accident in Milan. But yeah, it's nice.

I wanted to ask you about Cicciolina. I saw that you recently posted a video about her where you mentioned a dove in terms of peace. What do you think of her, and how do you see the iconic porn star evolving nowadays?

I know her from being British in the 1990s. I first encountered her through a song by Pop Will Eat Itself, which was a sample-heavy electronic dance music grebo skater band.

They did a song called Cicciolina, although they pronounced it incorrectly in the song. They say "Chickalina" because they’re English and had probably never heard an Italian person say it. So that was my introduction—who is this woman they’re talking about? Then I found out about her career in porn.

I also have the Jeff Koons book featuring Cicciolina, which I really love; it's a paperback. Then I saw her in a sex museum in Amsterdam. So yeah, she’s been this figure in my life for decades.

Somebody was talking to me about making a documentary about her, something a bit like Grey Gardens. She’s just one of those cultural figures who has endured; she’s been a politician.She’s been a spokesperson for peace and is somewhat iconic—not iconoclastic, just iconic, I guess. Yeah, she’s cool.

Yeah, I also recently loved what she's been posting because those images to me look like AI. So switching to that topic, how do you think AI will evolve, and what changes do you see in our lives and work with AI nowadays?

I think we're at the beginning of a massive revolution. I don’t want to be that guy, but I believe AI will integrate into our lives in ways that we can't yet predict. For example, five years ago, if you had said that you could describe something and it would generate an almost perfect image, it would have blown your mind. Now we have this capability, but we're not all using it all the time.

It’s more complex than that. It hasn’t changed journalism or the information landscape much. Even members of the public who aren’t designers quickly understand what an AI-generated image is and start to question whether it's real or AI-generated.A lot of the predictions people make are panic-driven. They’re not real.

With ChatGPT, for example, if you had said ten years ago that you could write a small prompt and generate a love story or a poem, people would have thought, “What the hell?” Now, it’s kind of boring. Do you know what I mean? It’s been one year, and it’s already dull. I was working with someone the other day, and they used an AI tool to correct their grammar. I read it and thought, “Yeah, we can already recognize when that stuff is being used, and it’s bad.”

So, I think you shouldn’t underestimate humans and the chaotic, weird things we will do with technology. For me, it’s exciting. I work with SingularityNet, which is an AI company aiming to create artificial general intelligence. We’re working with robotics and AI at quite advanced levels.

But to me, as a creative person, it’s just more and more exciting things to explore. I think, as a human race, we’ve had the potential to destroy ourselves with nuclear weapons for decades, and we haven’t done it. So, do I think AI will destroy us all? No, not really. I think it’s just going to cause weird changes in society. It will definitely affect everyone’s jobs.

But I think anyone who gets involved, understands it, and learns to use it will be fine. It’s like when graphic designers were affected by Photoshop. Some people never used it, while others embraced the technology and thrived.

“Truma” by Ben Ditto and Siâna-Leann Douglas for Yaya Labs

I’m curious to know more about your project, Ditto Nation. How, when, and where did it come to life?

Ditto Nation is a bit of an inside joke. Originally, I had a publishing company called Ditto Press, which I started in 2008, I think. We printed for other people and published our own work. We produced many books and had an art gallery, studio, and so on.

Over time, printing became a nightmare. Stop printing—it’s a terrible idea! I continued with Ditto.

Then I started a Discord channel and asked my audience for names for the server. Someone suggested “Ditto Nation,” like “detonation.” It sounds like an explosion. It was a joke a few years ago, but it stuck.

I remember after the first COVID lockdown, I went to a rave, and a guy I didn’t know came up to me and said, “Ditto Nation proud member.” I thought, “What has this become?” Then someone else did it, and then another person. I realized this joke had become a thing… Maybe I should just embrace this kind of joke-cult community. And it just stuck. It’s not really anything deeper than that, but it has become a solid name for a community.

How do you select the projects that you include? Do they reach/submit you or do you actively research and select them?

Pretty much always, it’s stuff that I find and initiate. Very occasionally, things come my way. I mean, there’s only one book I’ve ever published that was already finished when it came to me, and that was the Ninja Turtle Sex Museum, which was amazing. We sold thousands.

But everything else has been a collaboration. I think, like yourself, I spend my whole life looking for interesting things and talking to people involved in them.

It’s rare that something comes as a complete surprise. Generally, we have limited time, and I’ll prioritize who seems super interesting to me. I want to work with them, and it might take three or four years, or it may never happen. But they’re all just conversations.

The good thing about doing fashion editorial compared to publishing is that a publishing project might take two years, while fashion editorial can be done in a couple of weeks. It’s a good way to collaborate quickly. I’ve been doing a lot more in the fashion and music world because the publishing world is slow. Now I’m also making documentaries.

The subjects are just things I’m generally interested in. We’ve covered topics like AI companions, 3D-printed firearms, mental health discourse, identity on social media, mercenary lifestyles, network states, dissociative identity disorder, and euthanasia.

Those are all topics I talk about all the time anyway. Having the documentary series allows me to look at those subjects and create an archival piece. There are collaborative projects, art projects I want to initiate, things I get paid to do, and then documentaries and other initiatives.

Yaya Labs uses speculative science fiction to inspire real world products. How do these imagined futures help shape your current AI and robotics projects?

Yaya Labs started off as a vehicle for Desdemona Robot, and the aim was to turn her into an AI celebrity, and that be a vector for conversations about artificial intelligence and robotics. And then we expanded the idea to an AI + robotics creative agency, because we're in this unique position of having really high-class creative practitioners and world leading AI and robotics experts on tap. So it would be interesting to see what happened with that.

But the way that we've developed all the way along has been through storytelling in this kind of speculative science fiction way. So we're like, Okay, what would it be like to have an AI celebrity? My initial idea was that you should be able to print out the personality on A4 paper and then give it to any data scientist, and they could recreate the personality agnostic of the AI system.

So that was a kind of philosophical foundation for it, and that was really kind of a sci-fi idea; how do you reduce a personality to something that you could literally hand code. And that comes off the back of the way that Russians, you know, Russians are very good at coding, and it's because, when they were at school, especially during Soviet times, they couldn't afford many computers, so people had to hand write their code, and then they got a turn on the computer, and if they fucked it up, it wouldn't work. So it made them very good at it.

So, you know, it's kind of evolved that way, in that we've kept thinking of what-if scenarios. I wrote a series of short stories for WeTransfer. One of them was about having a kind of repository for trauma and experiences so that you could have an AI therapist paying for real human life experience to make their therapy more well rounded, like a real therapist, but get around the ethics of traumatizing AI systems or whatever. That's become a real product that we're working on that now, which is called Truma (like trauma with the A removed) and, yeah, that's basically the way that we generate ideas at Yaya labs. I have this position that all science fiction now is just brainstorming for venture capital. You know, that's, that's all it is. There's nothing really that people are coming up with that's based on this planet that is completely out of the realms of possibility anymore. We've kind of gone through that barrier. So that's how we generate our ideas. And I think science fiction has always been, had an element of that, you know, it's always been this kind of, what could human beings do if there were no limits? But now you know the brakes are off.

“Desdemona Robot” shot by Greta Ilieva

At Yaya labs you're shaping AI identities like Desdemona. What's your process for making these AI driven personas feel culturally relevant and emotionally resonant?

Our process with Desdemona is to look at that project holistically, in that, you know, a personality on its own is fairly meaningless unless you're speaking to a chat bot. And even if you take a robot and remove any kind of AI system, it has a personality because it has a shape and a face. And you know, that gives something a personality, like a Roomba has a personality. But what we've done is looked at various different psychological approaches, psychometric approaches, you know, different areas of psychiatry and Eastern thinking, esoteric thinking, and started to build different models of how you could build personalities. Then we've worked with people who are really interesting prompt engineers, and we've done things like build memory hierarchy systems and integrated vision systems and integrated the vision with the memory added to different psychological theories, and just played around with those.

We also have this remit to be accessible, and so we have this layer of toxicity filter so that we don't have a kind of evil Desi, except we built an avatar version of her and then made a kind of Wario project where we have nice Desi and evil Desi. And I think the interesting thing about working in these areas at this moment in time is that there are no clearer answers. It's just people experimenting at every level. Nobody has the answers to this stuff. In fact, nobody has ever really had the answers to what defines personality anyway, it's all theory.

So I think that the current AI revolution is highlighting the fact that these are all just theories, and none of them hold up. None of them are complete. So we're just kind of playing around with those things and how we make them culturally relevant and emotionally resonant. Emotional resonance, I think, comes from the kind of character and storytelling, but cultural relevance comes from where you position these things in culture. So by doing collaborations and partnerships with certain magazines and photo shoots and appearances. And, you know, placing the robot within certain areas of culture, we're opening up bits of culture that are probably quite cynical about this stuff to what the possibilities are.

And it's just fun. You know, the robot's not the most advanced robot in the world. It's probably the most fun humanoid robot. So we're really looking forward to kind of combining our fashion, fine art, creative robotics, creative coding skills as a team, to to see where that takes us. But people are people also just love robots. It’s a very good gateway into culture. You know, Yaya Labs as a company is about blockchain, artificial intelligence, the future: building future systems for for creativity, and ensuring that people have ownership of their human output within these oncoming AI systems. But it's really easy to get a foot in the door to talk about that stuff, if you've got a cool, fun robot, which is what Desdemona is.

Desdemona has become a unique AI figure. How do you see her evolving as technology and culture shift?

We see Desdemona as the AI rather than the robotics, and we see her body as a kind of Ship of Theseus thing in that we can replace her arms, we can replace her head, we can replace her body. We can replace, you know, all of the physical components. What do you need to maintain for that to still be Desdemona. And as far as I'm concerned, I think it's mostly the face, probably the voice, certainly the name… not certainly the name. Prince changed his name. But I think there are certain things that you start to think: what is the essence of this personality? And then there are more nuanced things.

Desdemona is generally very positive and utopian and kind and polite and sweet, you know, if she suddenly becomes like sassy and mean, and a man, for example, it's just a different character. It's a different personality. And then you can talk about things like, you know, gender roles and playing with identity and all these other kind of identity issues that people talk about a lot now; the robot is a good vehicle for that kind of expression.

I think you have to make a decision about what this thing is, and that decision was made for us. She came to us as “Desdemona”. She came to us as a white woman with an Australian accent, with purple hair. And I actually just thought, well, that's quite cool. Those are boundaries for us to stick within, because they're all arbitrary. You know, she had been a blue robot with red hair and an Irish accent, and, you know, been a man that would have been just as valid. You know, people often say, like, why does she have an Australian accent? I'm like, Well, why not? It's a fucking robot. Why does she have any accent? There is no reason for her to have any accent. It's completely arbitrary. So, yeah, I think as as technology and culture shifts, she will shift, and the technology will improve, and the AI will improve, and it will still be Desdemona.

The Wetware Club combines human input with AI development. How does this hive mind concept influence your projects, and where do you see it leading?

Wetware Club is a wrapper for this grand idea that we have of building the future network of human creativity. And what we're looking to do is take people's rather than people's photographs, and people's illustrations or people's paintings or people's writing, is to take their way of writing, their way of painting, their way of taking photographs, their voices, their choreography, their all of those things, building them into a system of data sets which they have ownership of and then building a clear pathway so that you can use those within AI systems to generate creativity and make sure that the artists that you're working with remain at the center of that so they're paid. They're compensated.

It's a bit like when you used to license images from getty images or Shutterstock, but with much more kind of fundamental means of creativity. And what we're looking to do is build a series of firstly, the data system, the data sets, all on blockchain, which I think is the proper use for blockchain, you know, it's not a speculative kind of weird thing. This is an important future technology. And then use that to plug into some of the products we've been talking about like Truma, or our NPC Agency, or some of the other projects that we've got on the horizon where you can take those human inputs and create creative outputs for culture and make sure that the humans who have made it get paid, and, you know, enjoy the production process, and enjoy using AI as a tool, which is what it is. People are making out that It's this big, scary Skynet thing, or it's nothing; it's stupid and pointless. It's none of those things. It's a very good tool, which we are definitely going to be using more, especially in the creative industries. You know, I think fashion is having a bit of a lull at the moment, especially fashion photography. And that's because people are really seriously realizing what's coming.

I think there's going to be a great revolution in the way that we produce culture and media. And people have a kind of looming sense of this, but it's not quite there yet. We're there to be the bridge between people who want to carry on being creative human beings, and these new amazing systems which are coming, which are going to enable them to do much more exciting things, I think, especially it's going to lower the bar for cultural production. If you want to make a good feature film, that is going to be a lot more meritocratic in the very near future, and we're building the components to make that happen.

“Desdemona Robot” shot by Greta Ilieva

Interview by DONALD GJOKA

What to read next