Somnath Bhatt

With interests ranging from multimedia, technology and typography, New York based Somnath Bhatt’s art is intimately symbolic. Using an endless array of metaphors, Somnath manages to tap into the intersectional spaces of art and design where he plays a vital role in the discussion of creating outside the lines of western design etiquette. Somnath speaks to Coeval about ‘decolonisation’, his creative process and the arts scene.

In today’s hyper-connected digital world and it’s outpour of constant ‘content’, I am intrigued by the role work like yours (that draws from a historical and cultural place) can play in revitalising the importance of slowing down and acting with intention. How do you go about creating with intention? What does your process look like?

Especially through social media, today’s Artistic Self has merged with the mediated and “Quantified Self.” We merge “likes” and “views” and “followers” with the many other gamified values of our digital and analogue existence. We seek to measure and compare our

own performance, and also our relative status and competitive position — I definitely play into that. I don’t see myself as revitalizing anything. I think the idea of a constantly “revitalized” past, one in which history is uncritically resuscitated, is actually a retrograde vision of the future. Nostalgia is conservatism’s greatest weapon.

To be honest, I post on my finsta, see how much engagement it gets, and then repost the best performing items on main. I want to mention my other account, which I run with Ayqa Khan @southasia.art keeps getting shadow-banned whenever a guest curator posts slightly radical or abolitionist content. Something to think about, heh?

You were born and raised in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India by a family of social Activists – it is evident that this upbringing has naturally found its way into your work. However, you moved over to the United States for university. Has this changed the way you create?

Speaking with my aunt recently, made me realize: familial upbringings show us distribution of power, accountability, trusteeship – values useful for any functioning democracy. Most importantly, it shows us how to register a disagreement.

The way I create is always changing – that is a sign of a healthy practice. University in the United States didn’t change the way I create, I just became better at planning my time and verbalizing my thoughts. And, I get my interest in world music from my grandmother!

You’ve worked through various different mediums of graphic design, digital or through pattern making in Hyein Seo’s SS21 collection. How would you say the process and approach differs between them?

I am blessed with very kindred and generous collaborators – like two planets on the same orbit.

I always enjoy when my work finds unlikely audiences!

The fashion designer Hyein Seo, who is based between Seoul and Antwerp. It was incredible to see my drawings transformed into apparel, knits, and jewelry. I won’t say too much, since the entire collection will be out in February or March. Especially surprising was to see my work in a very goth-club-fashion context.

Hyein and I started by sharing books we enjoy. Team Hyein Seo had the most nurturing approach to this collaboration, and all the members of her team had such good taste and were super cute online. All of our work took place over Instagram and Google Hangouts. We listened to Midori Takada together, exchanged sketches, and kept up our morale. Each garment became a landscape, both of narratives and of fabric. We wanted to evoke an elegiac or hymnal feeling for the collection.

One unexpected discovery was of music that ultimately inspired this cross-medium collaboration. I kept thinking of three Gujarati songs:

ઉગ્યો ચાંદલિયો મધરાતે રઢિયાળી રાતે...

સૈયર મોરી રે ચાંદા ને પછવાડે સુરજ કે ‘દિ ઉગશે રે લોલ...

The third song was a lullaby my grandmother used to sing on the swing at night: તારા ધીમા ધીમા આવો… This lullaby invites the stars in the sky to come down and play. These songs are about the moon and the night sky, and they had an unexpectedly strong influence on our work. A part of my name, Som (સોમ) , also means the moon.

We hope that those who wear our garments can find those little stories. Hyein and I want to mention that our collaboration isn’t limited to this one collection… There is more to come!

Aside from designing, you are also a writer whose work focuses on interviewing other creatives. Do you feel the structural aspect of writing has influenced the way you create in other areas?

I am curious and selfishly love talking to people. The interviews and the writing enable that.

One of the promises I made myself in 2020 was to have a culturally relevant and research-based practice. One in which I develop my voice as a critic, ask questions, and engage with the field of design with a sense of poeticism. I want to write more about Indian craftspeople.

My writing process is more social than I anticipate – I am constantly in touch with other people and manage schedules to arrange an interview, which can take months of planning. I want to write humbly, lead with curiosity and carry a desire to learn. I want to thank brilliant editors like Elias Chen and Meg Miller for encouraging and refining the things I write.

What’s your favourite project that you have worked on?

I am going to mention two.

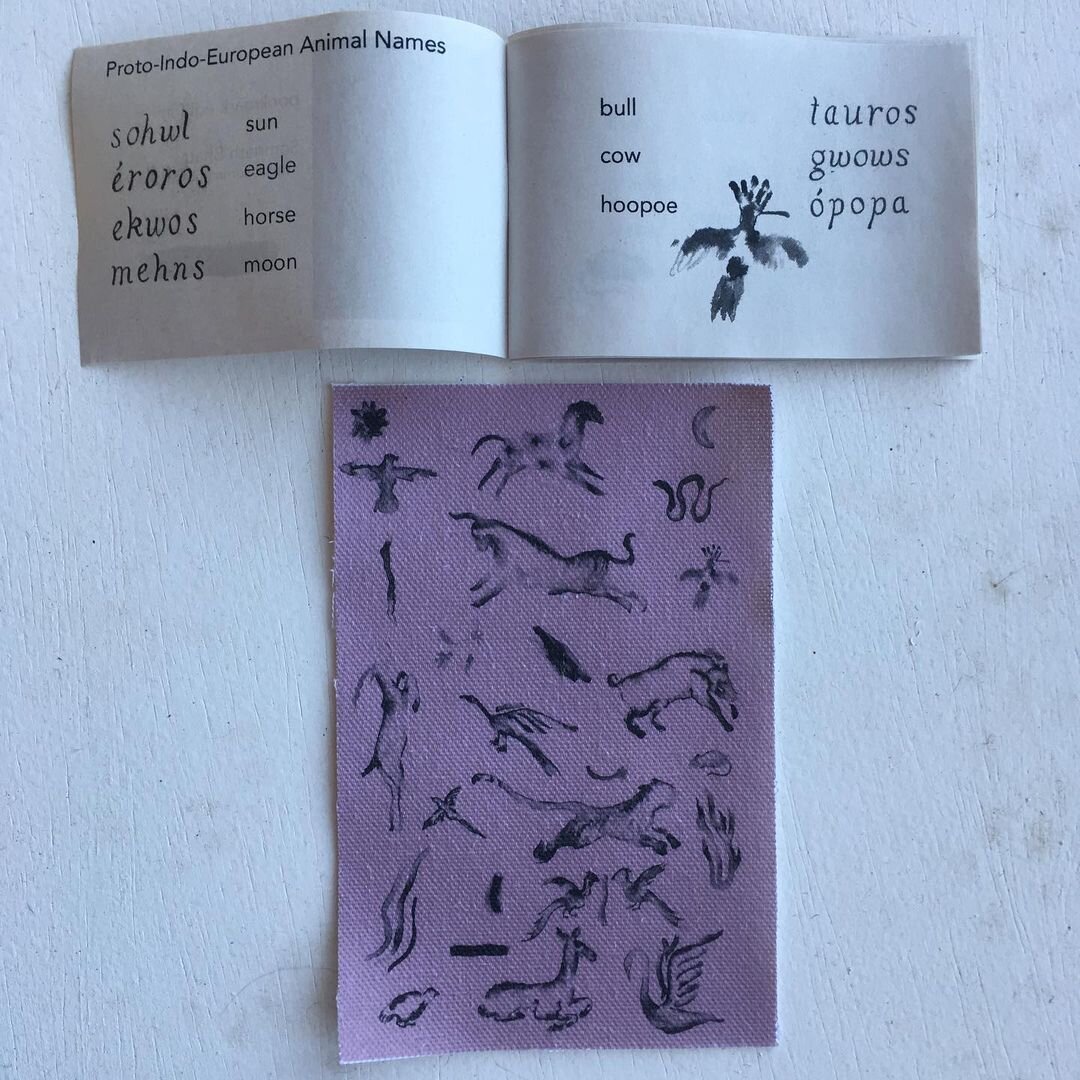

Śilpa: Catalogues on Craft is a particularly meaningful project I worked on with Malika Verma Kashyap of Border&Fall, a cultural agency shifting perceptions of Made in India with an evaluative and inquiring lens. Śilpa (शिल्प) is a Sanskrit word whose translation includes art, skill, craft, labor, ingenuity, rite and ritual, form and creation...

The Śilpa digital catalogues are an ongoing non-profit initiative by Border&Fall with the goal of connecting consumers directly to karigars (craft-makers). It strives to be a crowd-sourced directory of craft-makers in India. This is a form of direct action because it extends Border&Fall’s existing platform to a group of craftspeople who don’t frequently have direct contact with buyers online. It does the important, unprecedented work of creating a living database of contemporary craft workshops across various regions of India. Śilpa has published work by Mathew Sasa from Manipur, Khalid Amin Khatri from Bhuj, and Chato Kutsu from Nagaland, with many more to come.

The project connects people with singular makers, not brands – which is important because these craftspeople are often behind the scenes and their labor mostly anonymous. It is exciting to transition from viewing the hands that craft these objects to valuing the minds who make them.

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Another favorite project I’d like to send out intentions into the world for is an intimate collaboration with Hawa Arsala. We have been meeting for three weeks now. I will not reveal too much, for nazr purposes. It is a co-created investigation into Hawa’s multi-faceted creative praxis and philosophy. I am excited and eager to co-write and learn from the resources, insights, and tools Hawa brings as a strategist and creative director. Hawa’s interests and expertise range from fashion, creative direction, climate justice and race in both its study and its effects. She is able to cross-reference the “hyper-present with the emergent and now”. She has a love for semiotics, symbology and future-oriented world-building.

As someone who has been born and raised in the East but spent a brief amount of time in the West for University, I am intrigued by the distinct differences that the influences of social and cultural behaviours have on working culture between the two regions. You have expressed the importance of a collaborative model for design in your own work and the wider industry which I find might be a direct influence of your Indian background. Could you tell us a little bit about that and your thoughts on hyper-individuality in the Western space?

I would push back on this East v. West notion. I’ve been in the USA for 6 years which have been incredibly formative. I’m not sure if duration matters as much as the intensity of the exposure.

Art scenes are small and have the same amount of cliquiness anywhere. I don’t think the “creative culture” in India is any less hyper-individualistic than that of the States. The Indian art scene can be way more hierarchical, loaded with social baggage, and filled with gate-keepers. I am happy to see the shift away from disdain and devaluation towards creative labor in India. Art and design education are increasingly valued, as evidenced by the increasing number and enrollment of design schools in India since I was there. The Indian fashion and film industries have always maintained their homegrown integrity despite the homogenizing efforts of neoliberal globalisation. I love seeing the volume of radical thinking and work that my peers in India are coming up with – part of me wishes to be amidst them in India.

Like ‘sustainability’, ‘decolonisation’ has become a buzzword that has been used metaphorically to replace ‘diversification’. What are your thoughts on the word and the initiative for ‘decolonisation’ in design when it comes to removing ourselves from the teachings of a white-washed system?

Design only exists as a category to designate some makers as belonging to a genealogy of professionalized and industrialized making. It serves primarily to differentiate them from craftsmen. Design would need to negotiate its own history. “Decolonization” isn't like bathing in holy water or a quick rebrand.

In the last decade or so, “decolonisation,” which was originally a very powerful and controversial idea, has become very dilute from its original context. When we speak of decolonising, we very often mean simply the post-colonial.

There are no quick or easy antidotes. We entered into our current condition gradually, and to change this condition, we need to notice how the world feels and how it affects us. There were always alternate visions of our present reality, and I think we should look more closely at the configurations that don’t exist or didn’t come to fruition. Being open to those alternatives i.e collective ownership of land, economies of nurturance and collective aid, technocratic liberation theologies, as we live them now, constantly searching for them, this seems to me like one way out.

At the moment, the most urgent effort to be made toward decolonization is resisting fascism.

Some ways in which we can stop pandering to the white-gaze in a creative practice:

– Value craftspeople; foreground the manual labor that is the unacknowledged means of every design process

– Train a trust in skills and community, rather than consumerism

– Don’t center representation as the primary crux of resistance; prefer class solidarity and shared experiences of communion

– Place more value on reading, and supporting the intellectual and affective labor of contemporary non-Western thinkers, not just the dead ones

– Hold contradictions, reserve the right to defer solutions or to decline to answer

What do you hope to see from the creative or design fields in the future?

My dear friend Jake Sigl told me this: often the work we see from people called “creatives” is based on algorithms, numbers, sales, and revenue. And the interior lives of people are far more “creative” than their paychecks might indicate.

It is profound and enchanting to live inside a world whose richness is barely seen.

I hope that art workers can unionize and get decent healthcare. Abolish unpaid internships and underpaid positions. I want to see better avenues to help young creatives grow within the art world—ways forward that are not tokenizing.

I hope to include beauty gurus, cam performers, and TikTokers within the art/design canon.

Design Twitter has a tone problem. Communal sharing of Adobe Creative Cloud – like how we share streaming services. More thorough attribution in art and design labor; every project should have a list of contributors like the credits of a film. More shows like Grace Wales Bonner’s A Time for New Dreams and Rashmi Varma’s Matters of Hand – Inshallah!

Would you kindly leave us with an artist you are currently loving?

This answer requires not only artists but others who inspire me as well. People who come to mind are my beautiful museum co-workers from the Walker Art Center Alexandra Nicome, Jack Bachmann, Simona Zappas, and Amirah Ellison. These educators make experiencing art incredibly special and egalitarian. I’m obsessed with the curators Natasha Ginwala, Osei Bonsu, Shanay Jhaveri, Sadev Handy, and Shayari De Silva.

Some artists who I wholeheartedly admire from a distance:

– Rolando Hernández, an artist and curator based in Mexico City who works with sound and sonic archives

– Vidisha-Fadescha, founder of PartyofficeHQ, who examines the intersections of performance, desire, queerness, and caste

– Precious Okoyomon’s art and poetry

– The art collective The Packet in Sri Lanka, whose practice shows me the value of their statement: “We feel it is liberatory to continue to speak from the intimate, and to think in public.”

– Radio Al-Hara in Bethlehem

interview ANISHA KHEMLANI

What to read next